Advances in understanding conjunctival goblet cell traits and regenerative processes

阅读量:2853

DOI:10.12419/es24100501

发布日期:2025-03-10

作者:

Xiang Li (李想) ,王梦媛 ,陈翠婷 ,董诺

展开更多 '%20fill='white'%20fill-opacity='0.01'/%3e%3cmask%20id='mask0_3477_29692'%20style='mask-type:luminance'%20maskUnits='userSpaceOnUse'%20x='0'%20y='0'%20width='16'%20height='16'%3e%3crect%20id='&%23232;&%23146;&%23153;&%23231;&%23137;&%23136;_2'%20x='16'%20width='16'%20height='16'%20transform='rotate(90%2016%200)'%20fill='white'/%3e%3c/mask%3e%3cg%20mask='url(%23mask0_3477_29692)'%3e%3cpath%20id='&%23232;&%23183;&%23175;&%23229;&%23190;&%23132;'%20d='M14%205L8%2011L2%205'%20stroke='%23333333'%20stroke-width='1.5'%20stroke-linecap='round'%20stroke-linejoin='round'/%3e%3c/g%3e%3c/g%3e%3c/svg%3e)

关键词

conjunctiva

goblet cells

ocular surface

regenerative medicine

摘要

Conjunctival goblet cells are of great significance to the ocular surface. By secreting mucins—particularly MUC5AC—they play a pivotal role in stabilizing the tear film, safeguarding the cornea from environmental insults, and preserving overall ocular homeostasis. Over the past decade, remarkable progress has been made in understanding the distinctive biological characteristics and regenerative potential of these specialized cells, opening novel avenues for treating various ocular surface disorders, ranging from dry eye syndrome and allergic conjunctivitis to more severe conditions such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome. This review comprehensively examines the morphology, function, and regulation of conjunctival goblet cells. Advanced imaging modalities, such as transmission electron microscopy, have provided in-depth insights into their ultrastructure. Densely packed mucin granules and a specialized secretory apparatus have been uncovered, highlighting the cells’ proficiency in producing and releasing MUC5AC. These structural characterizations have significantly enhanced our understanding of how goblet cells contribute to maintaining a stable and protective mucosal barrier, which is crucial for ocular surface integrity. The review further delves into the intricate signaling networks governing the differentiation and regeneration of these cells. Key pathways, including Notch, Wnt/β-catenin, and TGF-β, have emerged as essential regulators of cell fate decisions, ensuring that goblet cells maintain their specialized functions. Critical transcription factors, such as Klf4, Klf5, and SPDEF, have been identified as indispensable for driving the differentiation process and sustaining the mature phenotype of goblet cells. Additionally, the modulatory effects of inflammatory mediators—such as IL-6, IL-13, and TNF-α—and growth factors, such as EGF and FGF, are explored. These molecular insights offer a robust framework for understanding the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying ocular surface diseases, wherein the dysregulation of these processes often results in diminished goblet cell numbers and impaired tear film stability. Innovative methodological approaches have provided a strong impetus to this field. The development of three-dimensional (3D) in vitro culture systems that replicate the native conjunctival microenvironment has enabled more physiologically relevant investigations of goblet cell biology. Moreover, the integration of stem cell technologies—including the use of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs)—has made it possible to generate goblet cell-like epithelia, thereby presenting promising strategies for tissue engineering and regenerative therapies. The application of artificial intelligence in optimizing drug screening and biomaterial scaffold design represents an exciting frontier that may accelerate the translation of these findings into effective clinical interventions. In conclusion, this review underscores the central role of conjunctival goblet cells in preserving ocular surface health and illuminates the transformative potential of emerging regenerative approaches. Continued research focused on deciphering the intricate molecular mechanisms governing goblet cell function and regeneration is essential for developing innovative, targeted therapies that can significantly improve the management of ocular surface diseases and enhance patient quality of life.

全文

HIGHLIGHTS

1.Critical Discoveries and Outcomes

This paper reviews the developmental structure of conjunctival goblet cells and examines their function on the ocular surface.

2.Methodological Innovations

It highlights recent advances in conjunctival goblet cell regeneration research.

3. Prospective Applications and Future Directions

Additionally, the article explores the potential of AI-assisted drug screening, biomaterial optimization, and interdisciplinary collaboration in advancing precision regenerative therapies for ocular diseases.

Introduction

The ocular surface, comprising a continuous layer of epithelial cells that includes the cornea, bulbar and palpebral conjunctiva, meibomian glands, and lacrimal glands, serves to protect the eye from external threats and ensures adequate light transmission to the retina. The tear film, which is crucial for ocular health, is maintained by secretions from these tissues, along with contributions from the nervous, endocrine, circulatory, and immune systems [1].

Conjunctival goblet cells, which are key producers of soluble mucin, play a vital role in preserving the tear film's smoothness and protective properties[2]. However, in ocular surface diseases, these cells often experience a reduction in both number and functionality. This review delves into the morphology and functions of conjunctival goblet cells, their changes in ocular surface diseases, and the regulatory mechanisms governing their behavior, encompassing gene expression and signaling pathways. Furthermore, It explores recent advancements in their regeneration through stem cell therapy, biomaterials, and gene therapy, addressing current challenges and outlining future directions.

Research on conjunctival goblet cells holds immense potential for the development of novel treatments that could significantly improve the quality of life for patients suffering from conditions such as dry eye syndrome and allergic eye diseases. By deepening our understanding and harnessing their regenerative capabilities, we have the opportunity to revolutionize the therapeutic approach to ocular surface disorders. This emphasis underscores the crucial role of conjunctival goblet cells in clinical ophthalmology and their contribution to pioneering new therapeutic strategies.

Anatomy and genesis of conjunctival goblet cells

Conjunctival goblet cells, which play a key role in the ocular surface epithelium, are responsible for producing and secreting mucin, a component critical for tear film stability and ocular surface moisture [3]. These cells exhibit a plump and rounded morphology, residing near the epithelial basement membrane and containing mucin granules enclosed within a cytoplasm abundant in Golgi apparatus, with nuclei close to the basement membrane [4]. Advanced imaging techniques, such as transmission electron microscopy, reveal these granules enclosed by a granular membrane adorned with "filamentous" structures, primarily composed of large, glycosylated mucins like MUC5AC and MUC5B, which are essential for ocular surface protection [5, 6]. The secretion of MUC5AC , vital for maintaining tear film integrity, is regulated by neurotransmitters, inflammatory agents, and hormones [3, 4]. Interactions between mucin granule membranes and MUC16 antibodies have been observed, though their roles are not fully understood [7]. Phalloidin staining highlights the presence of actin filaments at the apical edges of these cells, potentially aiding in mucin expulsion or pore closure [8]. Goblet cells establish tight junctions with adjacent epithelial cells, thereby enhancing tissue integrity, and display specific claudin expressions associated with ZO-1 in freeze-fracture images [9, 10, 11].

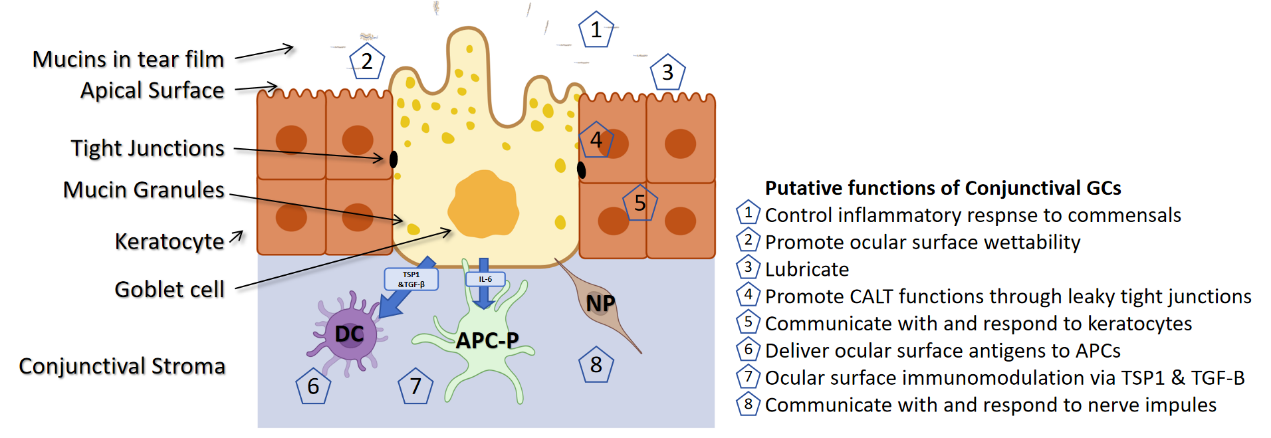

Research indicates that conjunctival epithelial stem cells posses the capability to differentiate into goblet cells, which are thought to originate from identical progenitors with bidirectional differentiation potential, found throughout the bulbar conjunctiva and limbus [12, 13]. Although corneal and conjunctival cells display distinct differentiation markers, the precise locations of goblet cell precursors have yet to be definitively identified [14]. A brief summary of the structure and function of conjunctival goblet cells is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1 The structure and function of conjunctival goblet cells [67]

Roles and control mechanisms of conjunctival goblet cell secretions

Conjunctival goblet cell products

MUC16, a membrane-anchored mucin present in both human and mouse conjunctival goblet cells [15], serves as a barrier against cell and pathogen invasion and is crucial for the adherence of MUC5AC to the ocular surface [5, 9]. MUC5AC, the primary mucin secreted by these cells, plays a vital role in lubricating and protecting the ocular surface. It predominates over MUC2 in goblet cells and has been implicated in conditions such as dry eye disease and keratitis [6, 16]. Another mucin, MUC5B, exhibits variable expression among goblet cells, with a distinct subset primarily dedicated to MUC5B production [9]. Studies involving mice deficient in either MUC5AC or MUC5B genes underscore their interchangeable roles in maintaining ocular surface health [9]. Furthermore, MUC1 and MUC4, also secreted by these cells, are predominantly localized in the conjunctiva and play essential roles in pathogen defense and maintaining barrier integrity. Notably, MUC4 expression decreases toward the center of the cornea [17, 18].

Functions of conjunctival goblet cells

MUC5AC, the predominant mucin produced by conjunctival goblet cells, imparts a unique viscosity to tears due to its complex glycoprotein structure [19]. This viscosity not only stabilizes tear flow but also establishes a consistent protective layer over the ocular surface. Furthermore, the extensive glycosylation of MUC5AC enables it to bind various pathogens, thereby serving as an active immune barrier. Conjunctival goblet cells respond to pathogens via surface Toll-like receptors (TLRs), specifically through TLR4 activation by bacterial lipopolysaccharides.This activation triggers a rapid immune response characterized by swift release of mucin and significant production of pro-inflammatory cytokines [20, 21]. Additionally, these cells modulate ocular immunity by responding to interferon-γ (IFN-γ) released by T cells, which enhances the expression of human leukocyte antigen-DR (HLA-DR). They also secret anti-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-10 (IL-10) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), aiding in the control of inflammation [22, 23]. Moreover, conjunctival goblet cells possess the ability to secrete growth factors like EGF and KGF and exhibit self-renewal capabilities. Following physical or inflammatory damage, they rapidly proliferate and collaborate with adjacent epithelial cells to promote cell migration at wound edges, thus accelerating the healing process. They also release matrix metalloproteinases that facilitate the remodeling of the extracellular matrix on the ocular surface, supporting both structural and functional recovery(Figure 1).

Maturation of conjunctival goblet cells

Conjunctival goblet cells initially appear in the lid margin area between the 8th and 9th weeks of human embryonic development. By the 11th to 12th weeks, these cells have matured and are capable of secretion, colonizing the palpebral conjunctiva. By the 20th week, they also populate the bulbar conjunctiva area [24]. As they mature, these cells migrate from the basal layer of the epithelium to the surface, where they actively secrete mucins. Following secretion, some cells enter a resting phase before resuming mucin synthesis, while others shrink and detach from the conjunctival epithelium after releasing mucin granules [25].

Factors influencing the proliferation of conjunctival goblet cells

Several Factors influence the proliferation of conjunctival goblet cell. Epidermal growth factor (EGF) regulates growth through its receptor (EGFR) by activating the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT pathways, thereby promoting cell proliferation [2]. Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) is another critical growth factor that enhances goblet cell proliferation [26]. Additionally, neurotransmitters and other factors, such as insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), also influence goblet cell activities and may impact their growth[27]. Furthermore, inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and interleukin-13 (IL-13), which increase during conjunctival inflammation, can affect goblet cell proliferation and functionality [28, 29].

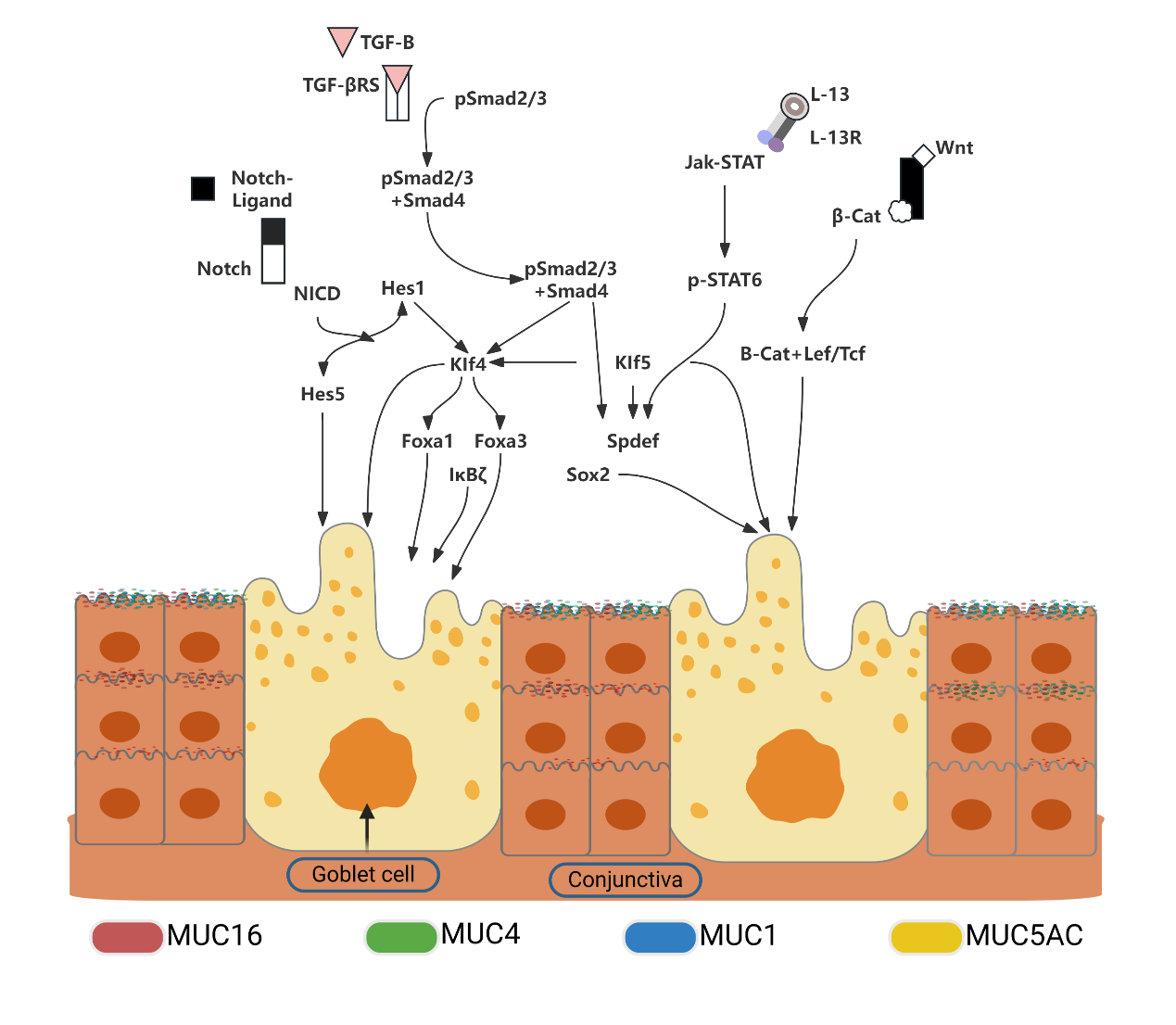

Main signaling pathways regulating the differentiation of conjunctival goblet cells

The Notch signaling pathway, which is essential for cell fate determination and tissue regeneration, plays a critical role in conjunctival goblet cell differentiation. Inhibition of Notch signaling through overexpression of Maml1 significantly impairs goblet cell differentiation, leading to increased proliferation and abnormal keratinization.This underscores the pathway's importance in maintaining epithelial integrity [30]. The loss of Klf4 and Klf5, vital downstream components of the Notch pathway, results in a substantial reduction in goblet cell numbers, highlighting their critical roles in differentiation [31-33].

Gene expression studies across different stages of conjunctival goblet cell development have identified transcription factors, such as Fox, Sox, Ets, and Krüppel-like as crucial during early stages. The loss of Klf4 function particularly emphasizes its direct influence on differentiation and regulation, prompting further research into its target genes within the conjunctiva [34].

The Wnt signaling pathway, which is vital in various physiological processes, also regulates conjunctival goblet cell differentiation. A deficiency in SPDEF, a key regulator within this pathway, results in decreased expression of essential Wnt genes, such as Frzb, Dixdc1, Wnt5b, and Wnt11, illustrating the pathway's role in differentiation. Additionally, KLF4 and KLF5 are known to enhance SPDEF promoter activity, indicating their regulatory impact [6].

TGF-β signaling, which is indispensable for epithelial homeostasis and regeneration, suppresses SPDEF expression, leading to excessive proliferation of both epithelial and goblet cells. The binding of Smad3 to the SPDEF promoter, which inhibits its transcription, elucidates TGF-β's specific regulatory mechanism [35].

In both airway and conjunctival epithelium, Foxa3 interacts with SPDEF, influencing goblet cell metaplasia. Specifically, in the conjunctiva, the absence of SPDEF significantly diminishes Foxa3 levels, demonstrating their interactive relationship [36]. The products of conjunctival goblet cells and the signaling pathways underlying their differentiation mechanisms are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2 The products and signaling pathways involved in the differentiation mechanisms of conjunctival goblet cells

Alterations of goblet cells in ocular surface pathologies

Various ocular surface inflammatory diseases, including dry eye disease, blepharitis, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome, are typically characterized by a significant reduction in conjunctival goblet cells and decreased levels of Muc5ac in tears [18, 35, 36]. Research has demonstrated a strong inverse correlation between the severity of these conditions and the number of goblet cells. Notably, dry eye diseas is marked by reduced goblet cell numbers and impaired functionality, which can be attributed to chronic inflammation, environmental factors, and altered tear composition [37]. Patients affected by this condition exhibit diminished secretory function and altered cell morphology, ultimately leading to tear film instability [38, 39]. In autoimmune disorders such as Sjögren's syndrome, ongoing inflammation impacts mucin composition, with cytokines like TNF-α and IFN-γ affecting goblet cell survival and secretion [40]. Nerve growth factor (NGF) has shown therapeutic potential in enhancing ocular surface healing, particularly in the context of dry eye disease. Furthermore, vitamin A deficiency has been linked to decreased conjunctival goblet cell function and numbers, adversely impacting ocular surface health [41]. These observation underscore the cruciall role of goblet cells in maintaining ocular health and provide insights into the management of dry eye disease.

In allergic conditions, conjunctival goblet cells adapt by enhancing their survival, proliferation, and secretion. Conditions like allergic conjunctivitis lead to increased goblet cells and excess mucin in tears [42]. Histamine and other allergens stimulate mucin secretion through pathways involving histamine receptor activation, which subsequently leads to increased epidermal growth factor receptor activity, AKT phosphorylation, and intracellular Ca2+ [43]. Chronic stress and repeated viral infections also trigger hyperproliferation and excessive mucin production in goblet cells, processes that are regulated by IL-4, IL-13, and EGF pathways [44, 45]. Additionally, IL-13 secreted by natural killer T cells enhances goblet cell differentiation by upregulating SPDEF [46, 47]. These findings highlight the precise regulation of conjunctival goblet cells in response to various external factors.

Tissue engineering in regenerative ophthalmology

Regulation of signaling pathways

The Wnt/β-catenin and Notch signaling pathways are of paramount importance for the growth and differentiation of conjunctival goblet cells. The Wnt pathway, which is integral to processes such as cell proliferation, differentiation, and migration, plays a central role in tissue repair during treatments of eye diseases. The stability and localization of β-catenin within this pathway are crucial for cell self-renewal and fate determination. Research indicates that modulating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway using small molecule compounds has the potential to enhance the proliferation of conjunctival goblet cells.

Similarly, the Notch signaling pathway is fundamental to cell differentiation and functional maturation. Alterations in this pathway significantly impact conjunctival goblet cell differentiation, with both activation and inhibition influencing their quantity and functional capabilities [34].

Influence of Cytokines and Growth Factors

Cytokines and growth factors, including fibroblast growth factor (FGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), and interferons, play pivotal in the regeneration of conjunctival goblet cells. Specifically, FGF and EGF stimulate the PI3K/Akt and MAPK signaling pathways, which are essential for promoting the proliferation, differentiation, and migration of these cells. Experimental evidence indicates that the external application of FGF can markedly enhance the proliferative capacity of conjunctival goblet cells.

Amniotic membrane and stem cell therapy

Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs) exhibit multipotent differentiation capacity and immunoregulatory attributes, rending them highly suitable for cell therapy applications. These cells can differentiate into conjunctival goblet cell-like cells and secrete cytokines and neurotrophins that facilitate the repair of ocular surface tissues, thus offering promising avenues for the treatments of various ophthalmic diseases. Transplantation therapy using conjunctival epithelial stem cells has demonstrated considerable therapeutic potential. When cultivated with specific differentiation inducers, these cells can transform into goblet cell-like entities, paving the way for novel strategies to repair ocular surface damage. Furthermore, research also highlights the crucial role of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in the pathology of limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD) by stimulating the self-renewal of conjunctival stem cells[48]. A notable breakthroug in regenerative medicine is the successful creation of functional conjunctival epithelium from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), marking a significant milestone in the induction of goblet cell under defined culture conditions [49]. Although autologous conjunctival transplantation is the preferred method for restoring the conjunctival epithelium, it is often constrained by technical hurdles. The nasal mucosa, which harbours goblet cells, exhibits potential in the management of severe dry eye syndrome. Conversely, goblet cell-free oral mucosa is less appropriate for ocular surface reconstruction [49, 50]. Amniotic membrane transplantation, widely employed for ocular surface regeneration, offers advantages due to its anti-inflammatory properties and suitability for thin, transparent applications. It promotes regeneration while preserving the integrity of conjunctival stem cells [51]. Advanced tissue engineering techniques enable the cultivation of conjunctival cells on scaffolds, providing alternatives transplantation options and broadening clinical applications through the co-culturing of epithelial cells and fibroblasts [52, 53]. Addressing severe cases of limbal stem cell deficiency involves combining autologous and allogeneic limbal margin transplantation to optimize the preservation of healthy stem cell and minimize immune responses [54]. Recent investigations suggest that mesenchymal stem cell injections can alleviate inflammation, enhance tear secretion, and augment goblet cell counts in dry eye syndrome, indicating new therapeutic pathways that may also restore vision [55].

Tissue engineering and regenerative medicine

3D printing and biological scaffolds

The integration of 3D printing technology with biological materials, including collagen, cellulose, and polylactic acid, facilitates the creation of a three-dimensional environment that closely emulates the physiological conditions of conjunctival goblet cells. These scaffolds exhibit exceptional biocompatibility and mechanical strength, both of which are essential for effective cell growth and differentiation. Research has shown that a small molecule mixture (3C), comprising Y27632, forskolin, and SB431542, preserves the stemness of conjunctival epithelial cells and promotes their proliferation, passage in culture, and differentiation into goblet cells [56].

Furthermore, a study has sucessfully developed a full-thickness 3D in vitro conjunctival model that supports goblet cell differentiation. By embedding type I collagen with fibroblasts and subsequently combining these with epithelial cells, researchers have fashioned a connective tissue equivalent that simulates the conjunctival environment. This co-culture technique yielded a stratified multilayer epithelium, resembling natural epithelium, with pronounced goblet cell differentiation. Experimental findings revealed that characteristics akin to in vivo conjunctiva were apparent at 15 and 20 days of culture. This successful development of this 3D in vitro model, which simulates human conjunctiva and induces goblet cell differentiation, offers a valuable tool for advancing ophthalmic research [57].

From evidence to precision: advancing goblet cell therapy

Despite the progress in our understanding of conjunctival goblet cells and their regenerative mechanisms, translating these insights into clinical therapies still requires further empirical validation. Future research efforts should concentrate on clinical case analyses and small-scale trials to substantiate the concrete benefits of these therapies for prevalent ocular surface diseases, such as dry eye disease (DED) and allergic ocular conditions, thereby paving the way for larger trials and personalized treatment strategies. In the context of DED, therapies utilizing stem cells enriched with goblet cell attributes or induced iPSC-derived epithelial-like cells have yielded promising outcomes, including prolonged tear film breakup time, reduced corneal and conjunctival staining, and improved patient-reported outcomes [49,58]. This preliminary data is crucial for identifying appropriate patient populations and formulating comprehensive clinical protocols. For allergic ocular diseases, like allergic conjunctivitis, locally applied biomaterial scaffolds combined with stem cell technology have proven effective in relieving symptoms such as itching, hyperemia, and discharge, while also enhancing tear film quality and patient comfort [59]. These cases illustrate that precise modulation of goblet cell function may decrease long-term dependence on anti-inflammatory medications. Beyond DED and allergies, these innovative approaches hold promise for treating severe ocular surface damage, such as that resulting from Stevens-Johnson syndrome, by restoring mucin secretion, enhancing corneal stability, and inhibiting scar progression [60]. They may also offer benefits in persistent DED cases following refractive surgery, aiding in stabilizing the tear film, accelerating epithelial healing, and improving visual quality [61]. Furthermore, the integration of biomaterial scaffolds and directed epithelial stem cell transplantation with growth and neurotrophic factors has demonstrated potential in enhancing the survival and differentiation of transplanted cells [62].

Future directions: interdisciplinary precision therapies

As research progresses, it is integrative conjunctival goblet cell studies with interdisciplinary technologies to facilitate the clinical translation of precision therapies. AI-assisted drug screening and personalized treatment decision-making have emerged as indispensable tools. By leveraging deep learning and machine learning algorithms, researchers can swiftly identify compounds that modulate goblet cell function, thereby accelerating the development of lead drugs [63]. AI-driven clinical models also integrate data from ocular imaging, tear composition, clinical symptoms, immune status, and gene expression to predict patient responses to regenerative therapies such as stem cell transplantation, gene editing, or biomaterial implants. This approach enables the customization of interventions to enhance efficacy and minimize side effects [64]. Furthermore, AI-driven computational models tackle technical challenges by optimizing biomaterial scaffold parameters to promote better goblet cell adhesion, growth, and differentiation [65]. Establishing unified quality control standards for cell viability, differentiation rates, and post-transplant survival rates is crucial for the development of clinically viable therapies [66]. By combining AI-assisted drug discovery with personalized care planning and materials science innovation, future research can more effectively bridge the gap between laboratory findings and clinical applications, promising more efficient, and precise regenerative treatments for DED, allergic ocular conditions, and other ocular surface disorders, ultimately improving patients’ quality of life.

Conclusion

Ocular surface health is heavily dependent on the function of conjunctival goblet cells. These cells produce and release a variety of bioactive substances, including mucins, trefoil factors, and defensins, which are essential for the protection ocular surface. The mucins secreted by these cells play a crucial role in maintaining integrity of the tear film and the optical properties of ocular surface, while ,also providing antibacterial and anti-inflammatory benefits. In conditions such as dry eye syndrome, impaired goblet cell function can lead to decreased mucin production, exacerbating the disease and increasing the risk of blindness. However, our understanding of the biological characteristics of these cells remains incomplete, hindering the development of treatments for common ocular surface disorders. Although recent studies have elucidated gene networks that influence the differentiation and function of these cells, some underlying mechanisms remains poorly understood. Future research should delve deeper into these mechanisms and regeneration methods for conjunctival goblet cells, with the aim of innovating treatment approaches for ocular surface disorders.

Abbreviation

Toll-like receptors (TLRs); interferon-γ (IFN-γ); human leukocyte antigen-DR (HLA-DR); interleukin-10 (IL-10); transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β); Bone marrow-derived; mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs); limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD); induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs); Dry eye disease (DED)Correction notice

None.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author Contributions

(I) Conception and design: Xiang Li

(II) Administrative support: Nuo Dong

(III) Provision of study materials or patients: Meng Yuan Wang

(IV) Collection and assembly of data: Cui Ting Chen

(V) Data analysis and interpretation: Xiang Li

(VI) Manuscript writing: All authors

(VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Funding

The work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81970771), and Project supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province, China (2020D027 ).

Conflict of Interests

None of the authors has any conflicts of interest to disclose.All authors have declared in the completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form.

Patient consent for publication

None

Ethics approval and consent to participate

None

Data availability statement

None

Open access

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons AttributionNonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license).

基金

1、The work was supported by grants from the National

Natural Science Foundation of China (81970771), and

Project supported by the Natural Science Foundation of

Fujian Province, China (2020D027).

参考文献

1、Yao KT. Study on the relationship between tear film and

optical quality after corneal refraction operation using

Optical Quality Analysis System[D]. Anhui Medical

University. 2020.

2、Dartt DA. Regulation of mucin and fluid secretion by

conjunctival epithelial cells. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2002,

21(6): 555-576. DOI: 10.1016/s1350-9462(02)00038-1.

3、Dartt DA, Hodges RR, Li D, et al. Conjunctival goblet

cell secretion stimulated by leukotrienes is reduced

by resolvins D1 and E1 to promote resolution of

inflammation. J Immunol. 2011, 186(7): 4455-4466. DOI:

10.4049/jimmunol.1000833.

4、Knop E, Knop N. The role of eye-associated lymphoid

tissue in corneal immune protection. J Anat. 2005, 206(3):

271-285. DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2005.00394.x.

5、Watanabe H, Fabricant M, Tisdale AS, et al. Human

corneal and conjunctival epithelia produce a mucin-like

glycoprotein for the apical surface. Invest Ophthalmol Vis

Sci. 1995, 36(2): 337-344.

6、Marko CK, Menon BB, Chen G, et al. Spdef null mice

lack conjunctival goblet cells and provide a model of dry

eye. Am J Pathol. 2013, 183(1): 35-48. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.03.017.

7、Gipson IK, Spurr-Michaud S, Tisdale A, et al. Comparison

of the transmembrane mucins MUC1 and MUC16 in

epithelial barrier function. PLoS One. 2014, 9(6): e100393.

DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100393.

8、Gipson IK, Tisdale AS. Visualization of conjunctival

goblet cell actin cytoskeleton and mucin content in tissue

whole mounts. Exp Eye Res. 1997, 65(3): 407-415. DOI:

10.1006/exer.1997.0351.

9、Gipson IK, Spurr-Michaud S, Argüeso P, et al. Mucin gene

expression in immortalized human corneal-limbal and

conjunctival epithelial cell lines. Invest Ophthalmol Vis

Sci. 2003, 44(6): 2496-2506. DOI: 10.1167/iovs.02-0851.

10、Yoshida Y, Ban Y, Kinoshita S. Tight junction

transmembrane protein claudin subtype expression and

distribution in human corneal and conjunctival epithelium.

Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009, 50(5): 2103-2108. DOI:

10.1167/iovs.08-3046.

11、Marko CK, Tisdale AS, Spurr-Michaud S, et al. The ocular

surface phenotype of Muc5ac and Muc5b null mice. Invest

Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014, 55(1): 291-300. DOI: 10.1167/

iovs.13-13194.

12、Wei ZG, Wu RL, Lavker RM, et al. In vitro growth and

differentiation of rabbit bulbar, fornix, and palpebral

conjunctival epithelia. Implications on conjunctival

epithelial transdifferentiation and stem cells. Invest

Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993, 34(5): 1814-1828.

13、Pellegrini G, Golisano O, Paterna P, et al. Location and

clonal analysis of stem cells and their differentiated

progeny in the human ocular surface. J Cell Biol. 1999,

145(4): 769-782. DOI: 10.1083/jcb.145.4.769.

14、Wei ZG, Cotsarelis G, Sun TT, et al. Label-retaining

cells are preferentially located in fornical epithelium:

implications on conjunctival epithelial homeostasis. Invest

Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995, 36(1): 236-246.

15、Blalock TD, Spurr-Michaud SJ, Tisdale AS, et al.

Functions of MUC16 in corneal epithelial cells. Invest

Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007, 48(10): 4509-4518. DOI:

10.1167/iovs.07-0430.

16、Jumblatt MM, McKenzie RW, Steele PS, et al. MUC7

expression in the human lacrimal gland and conjunctiva.

Cornea. 2003, 22(1): 41-45. DOI: 10.1097/00003226-

200301000-00010.

17、Hori Y, Spurr-Michaud S, Russo CL, et al. Differential regulation of membrane-associated mucins in the human

ocular surface epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci.

2004, 45(1): 114-122. DOI: 10.1167/iovs.03-0903.

18、Argüeso P, Balaram M, Spurr-Michaud S, et al. Decreased

levels of the goblet cell mucin MUC5AC in tears of

patients with Sjögren syndrome. Invest Ophthalmol Vis

Sci. 2002, 43(4): 1004-1011.

19、McNamara NA, Gallup M, Porco TC. Establishing PAX6

as a biomarker to detect early loss of ocular phenotype

in human patients with Sjögren’s syndrome. Invest

Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014, 55(11): 7079-7084. DOI:

10.1167/iovs.14-14828.

20、Redfern RL, McDermott AM. Toll-like receptors in ocular

surface disease. Exp Eye Res. 2010, 90(6): 679-687. DOI:

10.1016/j.exer.2010.03.012.

21、Dartt DA. Tear lipocalin: structure and function. Ocul Surf.

2011, 9(3): 126-138. DOI: 10.1016/s1542-0124(11)70022-

2.

22、Pflugfelder SC, Jones D, Ji Z, et al. Altered cytokine

balance in the tear fluid and conjunctiva of patients

with Sjögren’s syndrome keratoconjunctivitis sicca.

Curr Eye Res. 1999, 19(3): 201-211. DOI: 10.1076/

ceyr.19.3.201.5309.

23、Gipson IK, Argüeso P. Role of mucins in the function of

the corneal and conjunctival epithelia. Int Rev Cytol. 2003,

231: 1-49. DOI: 10.1016/s0074-7696(03)31001-0.

24、Li ZJ, Wang CJ. Focusing on the role of conjunctiva goblet

cell in maintaining the health of ocular surface. Chin J

Exp Ophthalmol. 2017, 35(2): 97-101. DOI: 10.3760/cma.

j.issn.20950160.2017.02.001.

25、Wang ZX, Sun XG. Research progress of conjunctival

goblet cells. Section Ophthalmol Foreign Med Sci. 2005,

29(4): 224-227.

26、Li S, Sack R, Vijmasi T, et al. Antibody protein array

analysis of the tear film cytokines. Optom Vis Sci. 2008,

85(8): 653-660. DOI: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181824e20.

27、Zhou L, Beuerman RW, Chan CM, et al. Identification of

tear fluid biomarkers in dry eye syndrome using iTRAQ

quantitative proteomics. J Proteome Res. 2009, 8(11):

4889-4905. DOI: 10.1021/pr900686s.

28、Nakamura T, Hamuro J, Takaishi M, et al. LRIG1 inhibits

STAT3-dependent inflammation to maintain corneal

homeostasis. J Clin Invest. 2014, 124(1): 385-397. DOI:

10.1172/JCI71488.

29、Contreras-Ruiz L, Regenfuss B, Mir FA, et al. Conjunctival

inflammation in thrombospondin-1 deficient mouse model

of Sjögren’s syndrome. PLoS One. 2013, 8(9): e75937.

DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075937.

30、Zhang Y, Lam O, Nguyen MT, et al. Mastermind-like

transcriptional co-activator-mediated Notch signaling

is indispensable for maintaining conjunctival epithelial

identity. Development. 2013, 140(3): 594-605. DOI:

10.1242/dev.082842.

31、Swamynathan S, Kenchegowda D, Piatigorsky J, et

al. Regulation of corneal epithelial barrier function by

Kruppel-like transcription factor 4. Invest Ophthalmol Vis

Sci. 2011, 52(3): 1762-1769. DOI: 10.1167/iovs.10-6134.

32、Young RD, Swamynathan SK, Boote C, et al. Stromal

edema in klf4 conditional null mouse cornea is associated

with altered collagen fibril organization and reduced

proteoglycans. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009, 50(9):

4155-4161. DOI: 10.1167/iovs.09-3561.

33、Swamynathan SK, Katz JP, Kaestner KH, et al.

Conditional deletion of the mouse Klf4 gene results in

corneal epithelial fragility, stromal edema, and loss of

conjunctival goblet cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2007, 27(1): 182-

194. DOI: 10.1128/mcb.00846-06.

34、Gupta D, Harvey SAK, Kaminski N, et al. Mouse

conjunctival forniceal gene expression during postnatal

development and its regulation by Kruppel-like factor 4.

Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011, 52(8): 4951-4962. DOI:

10.1167/iovs.10-7068.

35、McCauley HA, Liu CY, Attia AC, et al. TGFβ signaling

inhibits goblet cell differentiation via SPDEF in

conjunctival epithelium. Development. 2014, 141(23):

4628-4639. DOI: 10.1242/dev.117804.

36、Huang P, He Z, Ji S, et al. Induction of functional

hepatocyte-like cells from mouse fibroblasts by defined

factors. Nature. 2011, 475(7356): 386-389. DOI: 10.1038/

nature10116.

37、De Nicola R, Labbé A, Amar N, et al. Microscopie

confocale et pathologies de la surface oculaire: corrélations

anatomo-cliniques. J Français D’ophtalmologie. 2005,

28(7): 691-698. DOI: 10.1016/S0181-5512(05)80980-5.

38、Cvenkel B, Štunf Š, Kirbiš IS, et al. Symptoms and signs

of ocular surface disease related to topical medication in

patients with glaucoma. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015, 9: 625-

631. DOI: 10.2147/OPTH.S81247.

39、Lemp MA. Ocular surface disease. Arch Ophthalmol.

1984, 102(2): 194. DOI: 10.1001/archopht.1984.

01040030148008.

40、Contreras-Ruiz L, Ghosh-Mitra A, Shatos MA, et al.

Modulation of conjunctival goblet cell function by

inflammatory cytokines. Mediators Inflamm. 2013, 2013:

636812. DOI: 10.1155/2013/636812.

41、Sommer A. Vitamin A, infectious disease, and childhood

mortality: a 2 solution? J Infect Dis. 1993, 167(5): 1003-

1007. DOI: 10.1093/infdis/167.5.1003.

42、Zhong Y, Zhu JK, Wang LX, et al. Research progress

in characteristics of conjunctiva goblet cells and its

relationship with ocular surface health. Int Eye Sci.

2017, 17(9): 1667-1670. DOI: 10.3980/j.issn. 672-

5123.2017.9.15.

43、Dartt DA, Masli S. Conjunctival epithelial and goblet

cell function in chronic inflammation and ocular allergic

inflammation. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014,

14(5): 464-470. DOI: 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000098.

44、Park KS, Korfhagen TR, Bruno MD, et al. SPDEF

regulates goblet cell hyperplasia in the airway epithelium.

J Clin Invest. 2007, 117(4): 978-988. DOI: 10.1172/

JCI29176.

45、Chen G, Korfhagen TR, Karp CL, et al. Foxa3 induces

goblet cell metaplasia and inhibits innate antiviral

immunity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014, 189(3): 301-

313. DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201306-1181OC.

46、Chen G, Korfhagen TR, Xu Y, et al. SPDEF is required for

mouse pulmonary goblet cell differentiation and regulates

a network of genes associated with mucus production. J

Clin Invest. 2009, 119(10): 2914-2924. DOI: 10.1172/

JCI39731.

47、De Paiva CS, Raince JK, McClellan AJ, et al. Homeostatic

control of conjunctival mucosal goblet cells by NKTderived IL-13. Mucosal Immunol. 2011, 4(4): 397-408.

DOI: 10.1038/mi.2010.82.

48、Jang E, Jin S, Cho KJ, et al. Wnt/β-catenin signaling

stimulates the self-renewal of conjunctival stem cells and

promotes corneal conjunctivalization. Exp Mol Med. 2022,

54(8): 1156-1164. DOI: 10.1038/s12276-022-00823-y.

49、Nomi K, Hayashi R, Ishikawa Y, et al. Generation of

functional conjunctival epithelium, including goblet cells,

from human iPSCs. Cell Rep. 2021, 34(5): 108715. DOI:

10.1016/j.celrep.2021.108715.

50、Tang QM. Study on Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Stromal

Cell derived Factor-1 with Chitosan-based hydrogel for

Cornea Regeneration[D]. Zhejiang University. 2018.

51、Gera P, Kasturi N, Behera G, et al. Preparation and uses

of amniotic membrane for ocular surface reconstruction.

Indian J Ophthalmol. 2023, 71(8): 3119. DOI: 10.4103/

IJO.IJO_674_23.

52、Chen D, Qu Y, Hua X, et al. A hyaluronan hydrogel

scaffold-based xeno-free culture system for ex vivo

expansion of human corneal epithelial stem cells. Eye

(Lond). 2017, 31(6): 962-971. DOI: 10.1038/eye.2017.8.

53、Schrader S, Notara M, Tuft SJ, et al. Simulation of an

in vitro niche environment that preserves conjunctival

progenitor cells. Regen Med. 2010, 5(6): 877-889. DOI:

10.2217/rme.10.73.

54、Cheung AY, Sarnicola E, Govil A, et al. Combined

conjunctival limbal autografts and living-related

conjunctival limbal allografts for severe unilateral ocular

surface failure. Cornea. 2017, 36(12): 1570-1575. DOI:

10.1097/ICO.0000000000001376.

55、Lee MJ, Ko AY, Ko JH, et al. Mesenchymal stem/

stromal cells protect the ocular surface by suppressing

inflammation in an experimental dry eye. Mol Ther. 2015,

23(1): 139-146. DOI: 10.1038/mt.2014.159.

56、Xu L, Wang G, Shi R, et al. A cocktail of small molecules

maintains the stemness and differentiation potential of

conjunctival epithelial cells. Ocul Surf. 2023, 30: 107-118.

DOI: 10.1016/j.jtos.2023.08.005.

57、Schwebler J, Fey C, Kampik D, et al. Full thickness 3D in

vitro conjunctiva model enables goblet cell differentiation.

Sci Rep. 2023, 13(1): 12261. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-023-

38927-8.

58、Villatoro AJ, Fernández V, Claros S, et al. Regenerative

therapies in dry eye disease: from growth factors to cell therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2017, 18(11): 2264. DOI: 10.3390/

ijms18112264.

59、Rosa ML, Lionetti E, Reibaldi M, et al. Allergic

conjunctivitis: a comprehensive review of the literature.

Ital J Pediatr. 2013, 39: 18. DOI: 10.1186/1824-7288-39-

18.

60、Singh V, Shukla S, Ramachandran C, et al. Science

and art of cell-based ocular surface regeneration. Int

Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2015, 319: 45-106. DOI: 10.1016/

bs.ircmb.2015.07.001.

61、Qiu PJ, Yang YB. Early changes to dry eye and ocular

surface after small-incision lenticule extraction for myopia.

Int J Ophthalmol. 2016, 9(4): 575-579. DOI: 10.18240/

ijo.2016.04.17.

62、Messmer EM. The pathophysiology, diagnosis, and

treatment of dry eye disease. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015,

112(5): 71-81;quiz82. DOI: 10.3238/arztebl.2015.0071.

63、Stokes JM, Yang K, Swanson K, et al. A deep learning

approach to antibiotic discovery. Cell. 2020, 181(2): 475-

483. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.001.

64、Storås AM, Strümke I, Riegler MA, et al. Artificial

intelligence in dry eye disease. Ocul Surf. 2022, 23: 74-86.

DOI: 10.1016/j.jtos.2021.11.004.

65、Kumar A, Yun H, Funderburgh ML, et al. Regenerative

therapy for the cornea. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2022, 87:

101011. DOI: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2021.101011.

66、Witt J, Mertsch S, Borrelli M, et al. Decellularised

conjunctiva for ocular surface reconstruction.

Acta Biomater. 2018, 67: 259-269. DOI: 10.1016/

j.actbio.2017.11.054.

67、Swamynathan SK, Wells A. Conjunctival goblet cells:

Ocular surface functions, disorders that affect them, and

the potential for their regeneration. Ocul Surf. 2020, 18(1):

19-26. DOI: 10.1016/j.jtos.2019.11.005.

相关文章

Nathan J. Arboleda;Wen-Jeng (Melissa) Yao;Alex Theventhiran;Gene Kim,A narrative review of ocular surface disease considerations in the management of glaucomaRichard P. Gibralter;Vivian S. Hawn,Conjunctival flaps for the treatment of advanced ocular surface disease—looking back and beyondKatherine Chen;Mohammad Soleimani;Raghuram Koganti;Kasra Cheraqpour;Samer Habeel;Ali R. Djalilian,Cell-based therapies for limbal stem cell deficiency: a literature review