Application of anterior scleral thickness measurement in different ocular conditions using anterior segment optical coherence tomography: a systemic review

关键词

摘要

全文

HIGHLIGHTS

•AS-0CT provides a non-invasive method to measure anterior scleral thickness as an indicator of ocular health, which is an area with limited systemic reviews and signifcant research potential.

•AS-0CT may enhance clinical evaluation and research on ocular biomechanics, aiding in disease monitoring and progression understanding.

INTRODUCTION

The sclera is a crucial component of the eye.forming around 85% of the outer tunic of the humaneyeball. It is a connective tissue that consists of irregularlyarranged lamellae of collagen fibrils interspersed withproteoglycans and glycoproteins, serving as a protectivelayer that maintains the shape ofthe eyeball and providesan attachment point for the extraocular muscles.[1] It canalso influence the biomechanical characteristics of manyintraocular tissues, such as the cornea. A variety ofoculardisorders affect the sclera, such as scleritis, myopia, andcentral serous chorioretinopathy (CSC).[2-4] The seleralthickness may change with different ocular conditionsNowadays, limited imaging techniques are available forcomprehensively analyzing the whole structure of thesclera. Ultrasound biomicroscopy and anterior segmentoptical coherence tomography (AS-OCT) can be usedto visualize the anterior segment, including the anteriorsclera.[5] At present, OCT can also visualize the sclera othe posterior pole in highly myopic eyes.The advent of AS-OCT has revolutionized the evaluation of anterior ocular structures, including theanterior sclera.[6] AS-OCT offers high-resolution, non-invasive imaging that allows for precise measurementof anterior scleral thickness in vivo. Initially, the ASOCT was developed for the assessment of the corneaand anterior chamber. AS-OCT has expanded its utilityto include detailed visualization of the sclera, providingclinicians with valuable insights into the structuralintegrity and pathology of the eye. The growing body ofresearch utilizing AS-OCT underscores its importancein advancing our understanding of ocular biomechanicsand pathology, Recently, researchers have utilized AS.OCT to investigate the anterior scleral thickness not onlyin healthy eyes, but also in certain ocular disorders suchas keratoconus, myopia, CSC and others.[3-4,7] Given thecritical role of the sclera in maintaining the structuralintegrity of the globe and regulating choroidal venousflow and intraocular pressure, changes in scleral structurecan serve as indicators of susceptibility to various oculardiseases.[8-9] These changes are often reflected in scleralthickness measurements. Compared to ultrasoundbiomicroscopy, AS-OCT, with its superior axial resolution of 10 um, offers a more effective and precisetool for evaluating these conditions.[4,10]

The purpose of this systematic review is to identifand summarize the current literature regarding to theanterior scleral thickness measurement in different ocularconditions. By systematically evaluating the availableevidence, we aim to better understand the anterior scleralchanges in certain ocular diseases and to suggest futuredirections of research.

METHODS

Search strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conductedacross electronic databases, including PubMed, Scopusand Embase, to identify studies on measurement ofanterior scleral thickness using AS-OCT across differentocular conditions. The search strategy employed acombination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) termsand keywords related to "scleral thickness", "opticalcoherence tomography" and "anterior segment OCT" The search was limited to articles published in Englishand included studies from the inception of the databasesuntil January 2024. Bibliographies of selected articleswere also reviewed to identify any additional relevantstudies.The inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) useof AS-OCT to measure anterior scleral thickness; 2) quantitative measurements of anterior scleral thickness; and 3) full-text available.The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) involvedanimal subjects or cadaveric eyes; 2) used imagingtechniques other than AS-OCT; 3) no information aboutanterior scleral thickness; 3) case reports, reviews, editorials, or conference abstracts without full text.

Data extraction and risk of bias assessment

Data extraction was performed independentlyby two authors (Lihui Meng and Qianyi Yu) using astandardized data extraction form, The extracted dataincluded study characteristics (author, year of publication, country), population characteristics (age, sex, ocularcondition), AS-OCT parameters (device used), outcomes(mean anterior scleral thickness, standard deviation, measurement locations) and main study conclusions. Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved throughdiscussion or consultation with the corresponding author(Youxin Chen).For risk of bias assessment, we used the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) and the JBl Critical AppraisalChecklist for analytical cross-sectional studies to assess(as shown in supplementary file 1 and 2). The NOSincluded the following items: 1) the representativenessof the sample; 2) risk of bias in the measurementof exposures; 3) risk of bias in the measurement ofoutcomes; 4) risk of bias due to confounding factors. And the JBI Checklist included eight items includinginclusion criteria, study subjects, exposure, objective, confounding factors, strategies to deal with confoundingfactors, outcome measurement and statistical analysis.

Data synthesis

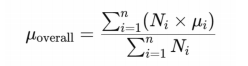

We did not perform any meta-analysis becauseof the heterogeneity of these studies. In our study,heterogeneity primarily arose from differences inthe sample characteristics (such as age, gender, andcomorbidities), variations in study equipment (differentAS-OCT devices), and inconsistencies in measurementlocations. Additionally, the analytical techniquesemployed in the included studies varied, which couldhave influenced the comparability of results. Given these factors, the variability between studies was substantial. and a meta-analysis would not have been appropriate. We summarized anterior scleral thickness in differentocular conditions in different studies and their mainfindings. Besides, we selected studies which have samelocation measurement in healthy eyes and CSC subjects, calculating the overall mean values (μoverall) and SD (σoverall) via the following formulas:

Ni is the sample size of subgroup i.

μi is the mean value of subgroup i.

n is the total number ofsubgroups.

oi is the sample size of subgroup i.

RESULTS

Main characteristics ofincluded studies

Except healthy subjects, this review included 11 different types ofocular disorders or conditions, includingmyopia, keratoconus, exotropia, retinal vein occlusion, CSC, scleritis or episcleritis, glaucoma, fuchs endothelialdystrophy, nanophthalmos, cycloplegia and intravitrealinjections. Researchers investigated the associationsbetween anterior scleral thickness with age, measurementlocations, diurnal variations, different disorders and localtherapies ( Table 1).Table 1. Summary of main characteristics of incuded studies.

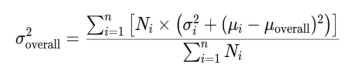

Figure 1 Screening process ofthe included studies

Risk of bias assessment

Supplementary file 1. Risk of bias assessments for the 32 included studies (NOS)

|

First author |

Publication year |

Selection |

Comparability |

Exposure |

Score |

|

Zinkernagel |

2015 |

3 |

1 |

3 |

|

|

Pekel |

2015 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

6 |

|

Schlatter |

2015 |

3 |

1 |

3 |

7 |

|

Ebneter |

2015 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

6 |

|

Buckhurst |

2015 |

4 |

1 |

2 |

7 |

|

Read |

2016 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

5 |

|

Woodman-Pieterse |

2018 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

6 |

|

Ha |

2019 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

6 |

|

Adiyeke |

2020 |

3 |

1 |

3 |

7 |

|

Dhakal |

2020 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

6 |

|

Kaya |

2020 |

4 |

1 |

1 |

6 |

|

Imanaga |

2021 |

4 |

1 |

2 |

7 |

|

Hau |

2021 |

2 |

1 |

3 |

6 |

|

Sung |

2021 |

4 |

1 |

1 |

6 |

|

Niyazmand |

2021 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

5 |

|

Lee |

2021 |

2 |

1 |

3 |

6 |

|

Park |

2021 |

3 |

1 |

3 |

7 |

|

Fernández-Vigo |

2021 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

7 |

|

Imanaga |

2022 |

4 |

2 |

2 |

8 |

|

Wang |

2022 |

4 |

1 |

2 |

7 |

|

Burguera-Giménez |

2022 |

2 |

1 |

3 |

6 |

|

Li |

2023 |

4 |

1 |

2 |

7 |

|

Zhou |

2023 |

4 |

1 |

2 |

7 |

|

Mohapatra |

2022 |

4 |

1 |

3 |

8 |

|

Korkmaz |

2023 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

6 |

|

Aichi |

2023 |

4 |

1 |

3 |

8 |

|

Fernández-Vigo |

2023 |

4 |

1 |

2 |

7 |

|

Yildiz |

2023 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

6 |

|

Fernández-Vigo |

2023 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

6 |

|

Korkmaz |

2023 |

2 |

1 |

3 |

6 |

|

Burguera-Giménez |

2023 |

3 |

1 |

3 |

7 |

|

Teeuw |

2023 |

4 |

1 |

2 |

7 |

Anterior scleral thickness in healthy eyes

Table 2. Anterior scleral thickness of healthy eyes (included in the calculation)

|

First author |

Publication year |

Nationality |

Sample size (Healthy) |

Age (Healthy) |

Gender (M:F,healthy) |

OCT device |

0mm-SS-T (μm) |

1mm-SS-T (μm) |

2mm-SS-T (μm) |

3mm-SS-T (μm) |

0mm-SS-N (μm) |

1mm-SS-N (μm) |

2mm-SS-N (μm) |

3mm-SS-N (μm) |

|

Buckhurst |

2015 |

United Kingdom |

74 (74 eyes) |

27.7±5.3 |

28:46 |

Visante AS-OCT (Zeiss) |

731±64 |

666±57 |

659±61 |

673±65 |

698±63 |

674±63 |

690±62 |

712±57 |

|

Adiyeke |

2020 |

Turkey |

35 (70 eyes) |

57.9±13.8 |

18:17 |

SD-AS OCT (Heidelberg) |

702.0±30.8 |

659.0±28.4 |

649.0±22.2 |

655.0±24.9 |

665.3±24.2 |

651.9±21.7 |

655.9±26.7 |

682.8±21.9 |

|

Fernández-Vigo |

2021 |

Spain |

596 (596 eyes) |

42.6±17.2 |

258:338 |

SS-AS OCT (Topcon) |

556.5±60.7 |

522.4±65.7 |

513.3±67.3 |

548.8±71.9 |

546.8±63.4 |

558.4±71.5 |

574.4±71.6 |

590.1±76.6 |

|

Burguera-Giménez |

2022 |

Spain |

50 (50 eyes) |

29.02±9.58 |

14:36 |

Casia 2 (AS SS-OCT; Tomey) |

|

522±65 |

497±63 |

513±71 |

|

525±51 |

531±58 |

532±65 |

|

Li |

2023 |

China |

42 (42 eyes) |

39.1±12.5 |

18:24 |

SS-OCT |

767.48±104.28 |

558.43±87.99 |

560.29±84.29 |

589.29±91.62 |

690.76±68.69 |

524.98±59.00 |

554.88±47.07 |

564.26±55.06 |

|

Fernández-Vigo |

2023 |

Spain |

53 (53 eyes) Hispanic |

38.7±12.3 |

24:29 |

SS-AS OCT (Topcon) |

|

536.1±77.9 |

559.8±80.8 |

591.6±83.0 |

|

589.3±68.3 |

611.3±78.8 |

613.0±75.0 |

|

60 (60 eyes) Caucasian |

41.8±11.7 |

26:34 |

SS-AS OCT (Topcon) |

|

535.5±56.0 |

520.7±50.1 |

558.9±54.7 |

|

565.8±75.1 |

577.5±74.5 |

589.8±76.4 |

|||

|

Fernández-Vigo |

2023 |

Spain |

30 (60 eyes) |

NA |

NA |

SS-AS OCT (Zeiss) |

|

670±100 |

704±89 |

691±118 |

|

687±98 |

740±94 |

767±120 |

|

30 (60 eyes) |

NA |

NA |

SD-AS OCT (Heidelberg) |

|

691±99 |

666±87 |

691±74 |

|

682±99 |

707±84 |

719±69 |

|||

|

Korkmaz |

2023 |

Turkey |

25 (25 eyes) |

30.6±12.4 |

8:17 |

Casia 2 (AS SS-OCT; Tomey) |

718.4±40.1 |

522.5±24.7 |

527.2±39.9 |

|

697.5±46.0 |

512.3±34.4 |

529.6±34.2 |

|

|

Burguera-Giménez |

2023 |

Spain |

50 (50 eyes) |

29.0±9.6 |

14:36 |

SD-AS OCT (Heidelberg) |

|

522±65 |

497±63 |

513±71 |

|

525±51 |

531±58 |

532±65 |

1 mm-SS-T: Anterior scleral thickness at a temporal distance of 1mm from the scleral spur

1 mm-SS-N: Anterior scleral thickness at a nasal distance of 1mm from the scleral spur

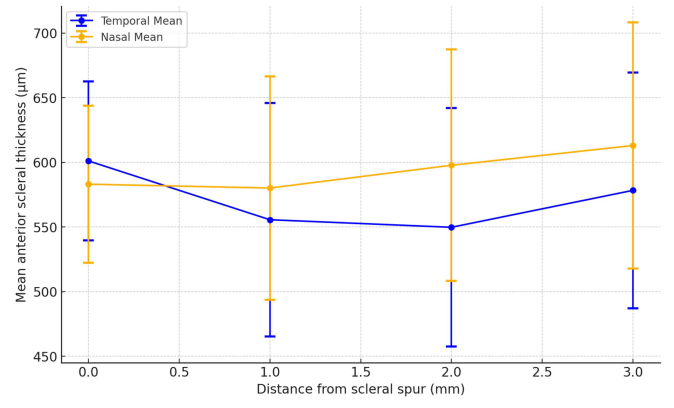

Figure 2 The overall mean temporal/nasal anterior scleral thickness in healthy eyes

Table 3. Anterior scleral thickness of eyes in two gender

|

First author |

Publication year |

Nationality |

Disease |

Sample size |

Age |

Gender |

0~6mm-SS-S (μm) |

0~6mm-SS-T (μm) |

0~6mm-SS-I (μm) |

0~6mm-SS-N (μm) |

0~6mm-SS-4q (μm) |

0~2mm-LB-4q (μm) |

|

Zhou |

2023 |

China |

Myopia |

93 (93 eyes) |

30.2±8.8 |

Male (n=37) |

495±42 |

603±48 |

575±62 |

569±67 |

559±50 |

|

|

Female (n=56) |

489±34 |

589±46 |

573±59 |

562±55 |

552±38 |

|

||||||

|

Teeuw |

2023 |

Netherland |

No |

107 (214 eyes) |

51.6±18.5 |

Male (n=48) |

|

|

|

|

|

552±57 |

|

Female (n=59) |

|

|

|

|

|

524±44 |

0~6 mm-SS-S: Average anterior scleral thickness at a superior distance of 0~6 mm from the scleral spur.

0~6 mm-SS-T: Average anterior scleral thickness at a temporal distance of 0~6 mm from the scleral spur.

0~6 mm-SS-I: Average anterior scleral thickness at a inferior distance of 0~6 mm from the scleral spur.

0~6 mm-SS-N: Average anterior scleral thickness at a nasal distance of 0~6 mm from the scleral spur.

0~6 mm-SS-4q: Average anterior scleral thickness of 4 quadrant at a distance of 0~6 mm from the scleral spur.

0~2 mm-LB-4q: Average anterior scleral thickness of 4 quadrant at a distance of 0~2 mm from the limbus.

Anterior scleral thickness in different ocularconditions

Scleritis and episcleritis

Inflammatory conditions like scleritis andepiseleritis show signifcant changes in scleral structure.Hau et al found the degree of vascularity and thickness ofsclera and episclera were different between episcleritis,scleritis and controls using AS-OCT or AS-OCTA.[16] AS-OCT may potentially be a useful tool in evaluatingpatients with scleral inflammation. And several studieshave investigated the conjunctival and scleral complex thickness in scleral inflammatory diseases.[2] We did not include them since they had no information about isolated anterior scleral thickness.

Myopia

50% studies proposed that myopic eyes often exhibited thinner sclera when compared to emmetropicand hypertropic eyes. For example, Dhakal et al foundthat the relative thinning of the anterior sclera alongthe inferior meridian with inereasing myopie degreecompared to other meridians (r = 0.27; P = 0.008).[17] The anterior scleral thickness can also be influenced by axial length, corneal thickness, intraocular pressure andeven Bruch’s membrane opening area[18] This thinningis associated with the elongation of the eye in myopia,contributing to the biomechanical instability ofthe sclera.However, the other 50% of publications did not findsignificant differences. For example, Pekel et al and Li et al found that the thickness of anterior wall struetures of myopic eyes has no statistical diference with healthyeyes.[3,19]

Keratoconus

In Keratoconus, anterior scleral thickness tendsto be abnormal. Yildiz et al. found that structuralfeatures of the cornea, sclera, and lamina cribrosa might be similarly affected in patients with keratoconusdue to similar collagen content of them.[7] Burguera-Giménez et al. reported that keratoconus eyes presentedsignificant thickness variations among eccentricitiesover the paracentral selera. The anterior scleral thicknesssignificantly varied with scleral eccentricity over thetemporal meridian (P = 0.009) in healthy controls, whereasin KC eyes, this variation was over the nasal (P = 0.001), temporal (P = 0.029) and inferior (P = 0.006) meridians.[20] However, Schlatter et al reported that the anterior scleralstroma thickness in keratoconus eyes is similar to that inhealthy subjects.[20]

Central serous chorioretinopathy

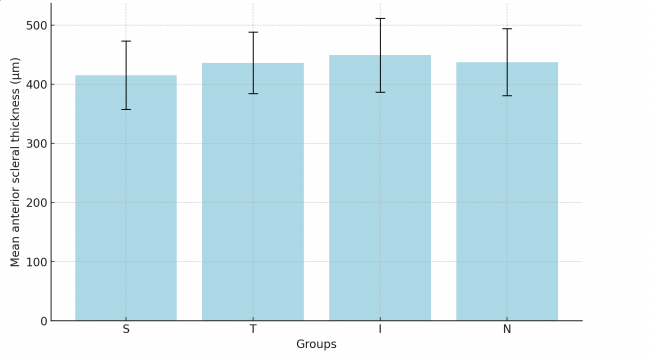

In CSC (Table 4 and Figure 3), 60% of the studiesWasfound that anterior scleral thickness was greater thancontrols and thought that thick sclera might have a role inmi ghtthe pathogenesis of CSC.[4,21] For example, lmanaga etal found that anterior scleral thickness was significantlygreater in CSC eyes than in normal control eyes at thesuperior ( 429.4±50.3 ) μm vs. ( 395.2±55.4) μm; P =0.005, temporal ( 447.7±45.7 ) μm vs. ( 396.5±64.1 ) μm; P <0.001, inferior ( 455.7±81.2 ) μm vs. ( 437.8±46.9 ) μm; P = 0.022, and nasal ( 454.9±44.7 ) μm vs. ( 416.6±51.2 ) μm; P = 0.001 points. 4 Besides, the anterior scleral thickness may alsohave a positive association with choroidal thickness.Lee et al found a positive association between subfovealchoroidal thickness and the sub-lateral rectus musclescleral thickness (r = 0.394, P = 0.031).[21] However, Mohapatra et al found that there is a significant inerease in posterior scleral thickness in CSC but no significantdifferences in anterior scleral thickness. [22] Aichi et al also found no significant differences between CSC and controls.[23]

Other ocular conditions

Some local therapies of the eye may lead to scleralchanges.For example, intravitreal injections may leadto thinner sclera if repeating in the same quadrant,[24-25] Zinkemagel et al.[25] reported that eyes with more than 30injections had thinner average anterior seleral thicknessin the inferotemporal quadrant ( 568.46±66 ) μm thanthe fellow eyes ( 590.6±75 ) μm, P = 0.003. Wang et al.[24] reported that injected eyes had a mean anterior scleral thickness of ( 588±95 ) μm versus ( 618±85 ) μm in fellownaive eyes ( P < 0.001). The anterior seleral thicknessshowed a signifcant reduction after using Prostaglandinanalogues ( P < 0.05), which might be associated with theinerease uveoscleral outflow.[26] And Korkmaz foundthat after cyeloplegia, there was a significant thinning ofanterior scleral thickness posterior to scleral spur in nasaland temporal quadrants ( P < 0.05) and a slight increasein anterior scleral thickness at the scleral spur but nosignificant difierences.[27]

In retinal vascular diseases, such as retinal veinocclusion, Adiyeke et al.[28] found that thickness of selerain CRVO eyes were significantly increased at scleralspur in all quadrants (P < 0.05). Also, in other cornealdiseases, such as Fuchs endothelial dystrophy, sclera wassignificantly thicker at 6 mm posterior to the seleral spurin all quadrants (P < 0.05).[29]

Noteworthy, AS-OCT has been applied in somesystemic diseases’ researches. For example, Kaya et alinvestigated the anterior scleral thickness in patients withsystemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and found that inSLE patients, the anterior sclera thickness is thicker atall distances compared with controls (P < 0.05).[30] Thisbroadens the application scope of AS-OCT.

Table 4. Anterior scleral thickness of eyes with central serious chorioretinopathy (included in the calculation)

|

First author |

Publication year |

Nationality |

Disease |

Sample size (CSC) |

Age (CSC) |

Gender (M:F, CSC) |

6mm-SS-S (μm) |

6mm-SS-T (μm) |

6mm-SS-I (μm) |

6mm-SS-N (μm) |

||

|

Imanaga |

2021 |

Japan |

Central Serous Chorioretinopathy |

40 (47 eyes) |

48.0±10.7 |

33:7 |

429.4±50.3 |

447.7±45.7 |

455.7±81.2 |

454.9±44.7 |

||

|

Imanaga |

2022 |

Japan |

Central Serous Chorioretinopathy (loculation of fluid (LOF)) |

98 (98 eyes) |

NA |

86:12 |

426.2±63.0 |

445.7±55.9 |

459.2±62.3 |

445.4±59.3 |

||

|

Central Serous Chorioretinopathy (non-loculation of fluid (non-LOF)) |

60 (60 eyes) |

NA |

44:16 |

395.1±52.1 |

414.9±47.4 |

428.8±49.6 |

414.3±55.9 |

|||||

|

Aichi |

2023 |

Japan |

Central Serous Chorioretinopathy |

115 (230 eyes) |

46.4±18.3 |

54:46 |

410.3±58.4 |

434.3±52.9 |

447.9±59.5 |

434.9±59.1 |

||

CSC : Central Serous Chorioretinopathy.

6mm-SS-S: Anterior scleral thickness at a superior distance of 6mm from the scleral spur.

6mm-SS-T: Anterior scleral thickness at a temporal distance of 6mm from the scleral spur.

6mm-SS-I: Anterior scleral thickness at a inferior distance of 6mm from the scleral spur.

6mm-SS-N: Anterior scleral thickness at a nasal distance of 6mm from the scleral spur.

DISCUSSION

In this systematic review, we provided a comprehensive overview of the curent understanding of anterior scleral thickness across various ocular conditionsusing AS-OCT. These studies collectively examined11 ocular disorders as well as healthy eyes. Variationsin anterior scleral thickness can indicate the preseneeand progression of ocular conditions. For instance.thinner sclera in myopic eyes suggests biomechanicalalterations, while increased thickness in conditions like active seleritis may reflects inflammatory responses.Additionally, age and diurnal variations further impactseleral measurements, ofering insights into their dynamicnature. The precision of AS-OCT in detecting thesesubtle changes enhances its utility in monitoring ocularhealth, potentially aiding early diagnosis and trackingdisease progression in clinical settings. The findingsunderscore the importance of anterior scleral thickness tobe a potential biomarker in ocular health.It is regarded that the anterior scleral thickness ispositively with age, This might be due to age-relatedchanges in seleral collagen and biomechanies.[11,13] Theobserved regional variations in anterior scleral thickness.such as the thicker inferior quadrant compared to otherquadrants, suggested that these variations could be linkedto the different mechanical stresses exerted on the seleraby ocular movements and external forces.[13] The diurnalvariations reported by Read et al indicated that the selera was not static throughout the day, which might be due tophysiological changes in ocular blood flow, intraocularpressure and other metries fuctuating with the cireadianrhythm,[14] The ethnic differences revealed by Femández.Vigo et al., with Hispanie patients showing highertemporal quadrant thickness compared to Caucasians, suggest that genetie or environmental factors may alsoinfluence scleral structure.[31] This finding may explainthe phenomenon to some extent that different ethics havequite different epidemiology in certain ocular disorders.Males had thicker anterior scleral thickness compared tofemales, but the significance of this phenomenon is notknown and could perhaps represent an anthropologicaldifference between two genders.[2]

The sclera has tight associations with other ocularstructures, such as the cornea, choroid and ciliary muscle.The anterior scleral thickness is associated with thebiomechanical corneal response metrics, Although themeasurement profiles did not differ between keratoconus and control groups in some studies, the inferior-superiorasymmetry differences demonstrated scleral changesover the vertical meridian in keratoconus, which needfurther investigation.[7,20,32] According to Korkmaz study,inhibition of forward inward movement of the ciliarybody by cycloplegia can affect anterior scleral thicknessvia causing a change in the mechanical force of theciliary muscle on the sclera.[27] In CSC, the associationbetween choroidal changes and anterior scleral thicknesshas been observed.[21]

The association between myopia and reducedanterior scleral thickness is well-documented in thereviewed studies, The thinning of the sclera, particularlyalong certain meridians, reflects the biomechanicalalterations associated with axial elongation in myopiceyes. This thinning compromises the structuralintegrity of the sclera, potentially exacerbating myopicprogression and increasing the risk of myopia-relatedcomplications.[33] However, the inconsistencies reportedby Pekel et al. suggest that anterior scleral thicknesschanges in myopia may not be uniform and coulddepend on additional factors such as the degree ofmyopia, axial length, and individual variations in seleralcomposition.[3,34]

In inflammatory conditions like scleritis andepiscleritis, the significant thickening of the scleraobserved in the reviewed studies underscores the utility ofAS-OCT in diagnosing and monitoring these conditions.AS-OCT was instrumental in identifying necrosisand scleral nodules in subclinical cases, and differentsubtypes of scleritis indicate different pathogenesis.Moreover, complete resolution of scleral inflammationcan be followed by OCT.[35] The ability of AS-OCTto detect subtle changes in scleral strueture makes it avaluable tool in distinguishing between different types ofscleral inflammation and in assessing the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions.

The findings related to CSC suggest a potential rolefor inereased anterior scleral thickness in the pathogenesisof the disease, possibly due to its association withchoroidal thickness. However, the lack of consensus, asseen in the studies by Mohapatra et al. and Aichi et al. indicates that further investigation was required to elucidatethe exact relationship between anterior scleral thicknessand CSC.[22-23,36] The potential influence of other factors, such as intraocular pressure and choroidal circulation, should also be considered in future studies.

The impact of local therapies, such as intravitrealinjections and the use of prostaglandin analogues, cycloplegia on anterior scleral thickness further broadensthe clinical relevance of anterior scleral thicknessmeasurements. The observed thinning of the sclerafollowing repeated injections or chronic medication usesuggests that these interventions may have unintendedeffects on scleral integrity, which could influencetreatment outcomes, particularly in patients requiringlong-term therapy, This may remind clinicians to monitoranterior scleral thickness in patients undergoing suchtreatments to prevent adverse effects.

The variations in anterior scleral thicknessobserved in conditions like retinal vein occlusion, Fuchsendothelial dystrophy, and systemic diseases like SLEsuggest that scleral changes are not confined to ocularpathologies but may also reflect systemic health. Thethicker sclera in SLE patients, as reported by Kaya et al, implies that systemic inflammatory or autoimmuneprocesses could impact scleral structure, providinga potential link between systemic health and ocular manifestations.[30] This finding opens new avenues forresearch into the role of anterior scleral thickness as amarker for systemie disease.

Strengths of our systematic review include that this topic was the first time to report. And we followedthe strict protocol in the synthesis process. However,there was significant variability in the standards usedacross studies, particularly in relation to diagnostictools and measurement techniques. For example, AS-OCT equipment from different manufacturers can yieldslightly varying results due to differences in resolutionscanning protocols, or imaging software. Additionally, measurement techniques are often not uniformly appliedacross studies, which can lead to inconsistencies inthe data. Standardization of these tools and methodswould not only enhance the accuracy and consistencyof measurements but also facilitate better comparabilityacross studies. Establishing standardized protocols for AS-OCT imaging, measurement analysis, and reporting could significantly improve the reproducibility ofresearch findings and lead to more robust conclusionsin future studies. Our analysis was limited due to thehigh risk of bias and heterogeneity of included studies,which preclude the further statistical analysis and poolingdata for meta-analysis. Specifically, variations in patientcharacteristics (e.g., age, gender, comorbidities andethnicities) and study equipment (e.g., SD-OCT vs. SS-OCT) could introduce bias or lead to divergent findings.To better understand the robustness of the conclusions, it would be useful to evaluate how such heterogeneitymight affect the outcomes with large sample size in thefuture.

To advance future research in this area, severalcritical steps should be taken to tackle the deficienciesidentified in the current literature. These steps include 1) measuring same locations in cohort studies; 2)conducting research in a large sample size andmaximizing the representativeness; 3) use design suchas matching, and analytic strategies (multivariableadjustment, propensity score matching, or inverse probability weighting)to control for potentialconfounding factors; 4) conducting subgroup analyses orsensitivity tests to assess the consistency of results acrossdifferent settings or groups; 5) promoting well-designedstudies to investigate anterior scleral thickness in diferentage group, gender group and different ocular conditions.

In conclusion, this systematic review underscoresthe significant role of anterior scleral thickness inocular health and disease, as well as the growingimportance of AS-OCT in clinical practice. Continuedresearch into anterior scleral thickness, with a focus onstandardization, longitudinal analysis, and multimodalimaging, will further advance our understanding ofscleral biomechanics and its implications for ocular andsystemic health.

Correction notice

NoneAcknowledgement

NoneAuthor Contributions

(I)Conception and design: Lihui Meng and Qianyi Yu(II)Administrative support: Jingyuan Yang and YouxinChen

(III)Provision of study materials or patients: Allauthors

(IV)Collection and assembly of data: Lihui Meng andQianyi Yu

(V)Data analysis and interpretation: Lihui Meng and Qianyi Yu

(VI)Manuscript writing: All authors

(VII)Final approval of manuscript: All authors